Several founders reached out after reading my article on full-stack climate startups asking about recurring lessons from the companies I've invested in or observed. Specifically, they wanted to know what distinguishes the best full-stack climate startups from average ones, given the unique challenges in this space. This essay reflects on the common threads through the best full-stack startups.

Prioritise customer over technology

The common founder logic in the early days of building a full-stack startup follows this pattern: because our product can sell into a large market, de-risking technology is the primary focus. There seems to be this phased approach to company building where technology comes first, then once at prototype or pilot, a full-stack startup spends time on commercial progress. As Kevin Costner famously said in Fields of Dreams, "If you build it, they will come."

Whilst prioritising the biggest risks early is what startups should do, an overemphasis on technology versus the customer has proven to be bad strategy. More successful full-stack startups are proving that the conventional startup wisdom of getting product into customers' hands as early as possible is good strategy.

Antora Energy is a great example of this. While they're a thermal energy storage company decarbonising industrial heat and power today, this wasn’t exactly where they started. Antora’s first technology breakthrough was their novel thermophotovoltaic (TPV) cells that became the world’s most efficient solid state heat engine at converting heat back to electricity. Based on this technology breakthrough, the initial go-to-market plan was that this technology could solve the 100+ hour long-duration energy storage need. However, by prioritising customers over technology, they realised that industrial heat applications were a better first market. There’s an urgent buyer that needs to displace natural gas with a cost competitive, zero-carbon alternative. Whilst LDES remains a potential use-case for Antora’s technology, it’s likely they wouldn’t have been able to move at the speed they have in this vertical. Antora have gone on to raise $200m since focusing on industrial heat, deploying their first commercial system at the end of 2023.

Fervo Energy provides another compelling example of customer centricity. Instead of building a full-scale demo, Fervo's first commercial deployment was a small 3.5MW addition to an existing geothermal operator. As Sarah Jewett at Fervo explained, “We said: we have a proposal to increase the power production at your site. You will put no capital to work. You will only pay us in the event that we actually do produce hot geothermal fluid that you can generate power with, on a metered basis. You will pay us for that fluid on a metered basis. We are going to go test our technology on the outside of your field… They didn’t have to put anything at risk at the front, but they were able to benefit from the upside at back.” This emphasis on customer early meant that Fervo had a commercial deployment 5 years from their founding in 2017.

Shifting early company building from purely technology development to balancing customer success challenges conventional thinking that early rounds of capital are only for technical derisking milestones.

Go small to go big

The best full-stack climate startups tend to plan strategy in master plans. While the vision is large, they understand that sequencing is important. This manifests in starting with high-value, low-volume products.

This contrasts with less successful full-stack startups that focus from day one on scaling technology to solve the largest possible market. Climate founders are mission-driven and can be pushed by investors to focus on the largest market first. This is bad strategy. The largest market often generates the lowest revenue per unit, meaning the startup needs large scale before generating significant revenue. This leads founders and investors to believe that some technology types need "patient capital" – investors who believe in the technology before commercial proof points. While such capital exists, it's finite, and for the majority of venture and growth equity needed for early commercialization, a startup needs a reasonable path to scale within 10 years of founding.

A better approach, demonstrated by the best full-stack startups, is finding customers they can serve with products that are competitive on price and performance while generating strong unit economics.

One of the best master plan thinkers is Vow. Their first product was Forged Parfait, a cultured Japanese Quail they sold in fine dining restaurants in Singapore earlier this year. They did this in less than five years with $56M in funding – half the time of their competitors and at a time when less than 10% of their competitors are selling to customers. Their success stems from identifying customers they could serve at a price point that generated good unit economics with their current technology.

Solugen is also another startup that’s a master of sequencing and it’s clearly intentional - one of the company’s four values is Think Big Act Now, meaning they seek to solve the right problems, in the right sequence. Solugen’s early commercial traction has become somewhat folklore in climate tech - with their first $10,000, they built a PVC reactor to make hydrogen peroxide that they first sold to float spas. From there, they built a brand, Ode-to-Clean, to sell bioperoxide hand wipes. Next, they scaled to make wastewater products. Now, they are multi-product, multi-customer. It's amazing execution of high-value, low-volume progression down a cost curve.

Solugen’s founders have said one of the biggest things they learnt being customer centric early on was the importance of distribution. Gaurab Solugen’s co-founder/CEO has said “distribution of the chemical is just as important as the process of making it”. This one line is so powerful and applies to every full-stack climate startup: distribution > great product.

By completing a full loop of technology development to distribution, startups demonstrate their platform value. Revenue generation with good unit economics makes it easier for future funders to believe in step-function revenue growth as volume scales. Moving from zero to multi-million revenue after years of pure technology development is possible but presents a much harder case without distribution experience.

Augment the team early

Whilst hiring a team is always the biggest determinant of startup success - “the team you build is the company you build” - full-stack climate startups face a particularly steep inflection curve scaling across technology, regulatory, project development, supply chains and more.

What I’ve noticed with the best full-stack companies is that they prioritise hiring complementary skills over supplementary ones, and they do this early. Complementary hires bring new capabilities to the founding team, while supplementary hires simply scale existing capabilities.

Antora Energy demonstrates this well. The three founders recognised early that both policy and project development would be crucial to company success. Despite all being technical founders, two founders dedicated a large percentage of their time to policy and project development which has proved critical to company success. But it wasn’t only the founders scaling into this, they also hired complements. For project development, Antora acquired Medley Thermal in 2022 and Jordan Kearns, the founder of Medley, became Antora’s VP Project Development.

This shows the balancing act required: founders scaling into the many roles needed while bringing in complementary world-class talent.

Team augmentation alongside commercial proof points demonstrates readiness for scaling capital. While the scaling playbook post first-of-a-kind projects remains unique for each full-stack climate startup, two core elements persist: proving the technology works and augmenting the team with necessary skills as early as possible.

Build an operating system

Some say that Zucks “move fast, break things” philosophy doesn’t apply to full-stack climate startups because breaking things in the physical world has real consequences. While true, the best full-stack climate startups build an operating system to balance this risk and speed.

Operating system, in this context, means organisational principles that provide a framework for execution. Each system is unique, but the common thread is that successful full-stack startups integrate deeply across every company function from inception.

Tesla exemplifies this at scale, where deep integration across product, engineering, and design enables faster iteration than traditional automotive production lines. But there are many examples from the best emerging full-stack climate startups as well.

Solugen intentionally structures for deep integration, as VP Engineering Dr. Konrad Miller notes, "by integrating teams, as opposed to just writing reports and throwing them over the fence, we're able to bring these complex technologies to scale efficiently."

Vow demonstrates this integration effectively – their manufacturing, technology, marketing, product, and operations teams collaborate closely. This multidisciplinary approach enables their rapid progress, which they term "Vow speed."

Stegra’s (fka H2 Green Steel) CEO Henrik Henriksson says it also, more simply: “We aim for each project to take half the time and half the cost of the previous one, and keep reducing those figures as we move forward… our Boden project demonstrates real-world scaling—it took us four months to complete with roughly 40 people working fulltime. When we replicated this work at our Portugal site, it took just four weeks with five people."

This represents the core innovation of full-stack startups: coordination, not just technology. By completing the development-to-market loop collaboratively once, companies create platforms that accelerate future iterations.

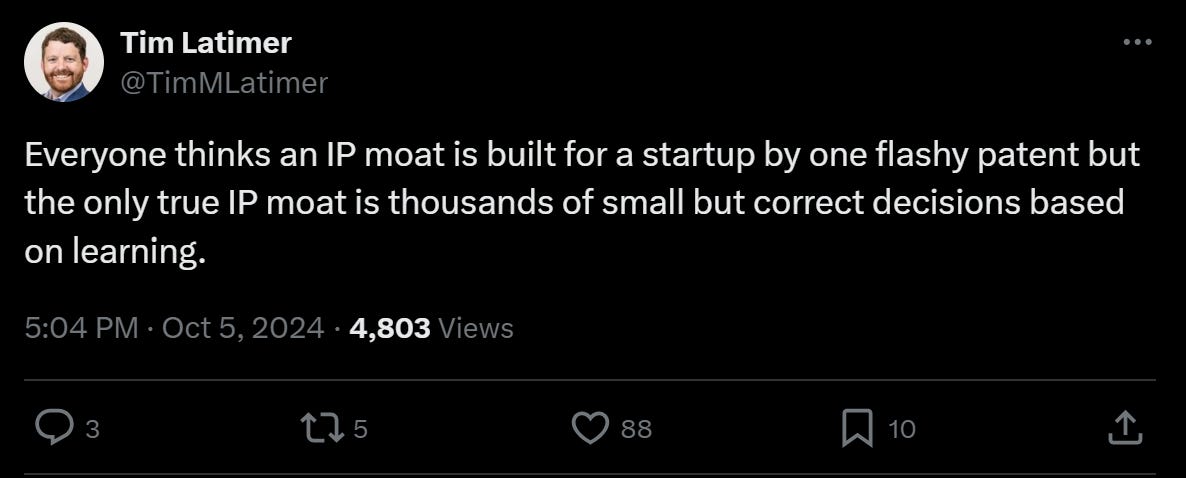

Tim Latimer Fervo’s founder/CEO says this best:

Twitter link

Founder… naughtiness

If you’re still following along, this last one is funny, I promise! To build a full-stack climate startup that transforms an industry, the challenge is herculean. Some think the best founders to transform an industry with a full-stack startup are those that don’t come from within that industry. The logic here is that it’s easier for an outsider to do the first principled thinking required. Though that may be true for some, a more common trait I’ve observed is founder naughtiness.

The startups I’ve discussed also show this. Solugen, when trying to sell Ode-to-Clean, strategically purchased every billboard along an executive's commute route to and from work, which resulted in him calling Solugen to ask what on earth the company did. Not kidding, go listen.

Vow's Mammoth Meatball campaign, where they used extinct animal DNA to demonstrate cultivated meat's potential, earned them an appearance on the Colbert Late Show (skip to 2:20):

A masterclass in guerilla marketing.

There’s a willingness to break rules that seems to be recurring in founder DNA of successful full-stack climate startups.

***

It’s unlikely every successful full-stack climate startup will do all the things I’ve mentioned above. Trying to replicate these for a certain startup is also bad strategy and not advised. But I think there are some learnings for full-stack startups from the companies I’ve mentioned above to think through.

As always, if you’re a founder building a full-stack climate company that’s looking to transform a physical industry, I’d love to hear from you.