I’ve been reflecting on the types of startups I believe have the best shot at decarbonising industries and becoming generational companies. Investing and supporting the founders building these companies is my ikigai and the one category type I keep building more conviction in over time is the full-stack climate startup.

The full-stack startup has been written about quite a lot in the last decade. Chris Dixon first dubbed the term in 2015. With re-industrialisation now in vogue, it’s being discussed more and more. Ian Rountree wrote a seminal piece in 2022 titled Full-Stack Deep Tech. I’ve read this piece that many times, and I hope now I don’t just parrot Ian but add to the public repository on the topic.

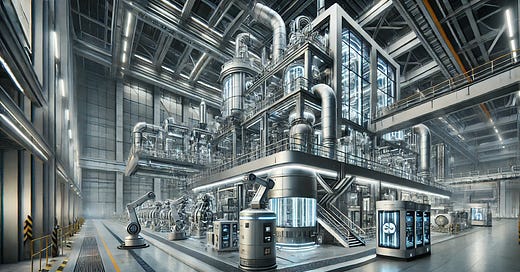

So let’s dive in! A full-stack startup is where instead of selling a technology to an incumbent, you become the incumbent. Full-stack startups don’t sell components into a product, their product is often the commodity produced by an end-to-end system incorporating their novel technology. More simply, full-stack climate startups sell decarbonised commodities, whether that be electrons or the many collections of molecules we use every day (e.g. minerals, chemicals, food).

Full-stack startups are interesting because they arguably go against conventional startup logic of going narrow in a core competency, building a wedge in an industry and then expanding from there. When I started investing I thought the same would apply in climate - i.e. it was possible to build generational companies that decarbonise large industries with a business model of selling components to the large incumbent producers. I now think this is next to impossible.

I’ve had the privilege to invest in a few full-stack climate startups (Antora, Lydian and Endolith) and whilst at different stages on the journey, all are heading towards being generational companies. On the flipside, I’ve seen great technology companies pursue the sell-to-incumbent business model and be less successful.

What prompted me to write this essay was a clarifying moment I had re-reading Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers. This line stuck out to me: “to assess which journeys are worth taking, you must first understand which destinations are desirable”. A lot of startup debate is often focused on execution > strategy, but when decarbonising an industry where major pivots are harder to do, day 1 strategy towards a “desirable destination” is table stakes.

The journey with a climate startup is that often they’re seeking to transform an old, established industry where consolidated incumbents sell end commodities and a highly fragmented value chain of suppliers sell to those incumbents. When looking at that industry, it’s logical for the conclusion to be: I need to sell my widget to that incumbent who can use their scale to distribute my product. For how can you compete against said incumbent who has sometimes trillions of sunk capex and optimised their value-chain to the nth degree? Whilst it’s understandable to start here, my belief today is it’s highly unlikely to become a generational company taking this route. It’s bad strategy.

When a founder develops a novel technology that has the potential to displace an incumbent, my favourite Helmer “power”1 is created - counter-positioning. Counter positioning is where a startup adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business. The smart incumbents respond by partnering with these startups - they hedge their bets against their existing production process.

In climate tech circles this is often viewed as a positive. There are many headlines that often read: “Startup developing novel technology disrupting X industry receives strategic investment from X industry’s largest producer”. Whilst I think this helps bring technology to market that may decarbonise the industry, I don’t think this strategy leads to the startup becoming a generational company.

Quick clarification side note, I think there's a lot of value in partnering with the buyers of your commodity when building a startup, just not producers of the same commodity.

If a startup’s business model is to sell a technology to an incumbent who makes the same commodity the startup’s technology makes, the upper limits of value creation are capped. They’re at the mercy of the incumbent's sales cycle, i.e. they move at incumbent speed vs startup speed. The incumbent retains all the pricing power, therefore material value capture is really hard. Even if a startup is great at raising capital, once they generate revenue and the unit economics of this business model become obvious to future funds, the logical outcome is either failure or M&A to the incumbent. Whilst this is an oversimplified journey, the point I’m illustrating is that this business model destroys the path to power.

Full-stack allows a startup to retain counter-positioning power and layer other powers that maximise value capture over time. Full-stack involves direct work by the startup to build their value chain and this knowledge often translates to a competitive advantage. Tesla is the often referenced case where “process power” may allow them to 10x the margins of conventional auto companies.

Tweet link

History provides several examples of full-stack startups that became generational companies that successfully commercialised technology innovations (although they didn’t identify as startups). Carnegie Steel and GE/Westinghouse are two that stick out for me:

Andrew Carnegie scaled the Bessemer process that transformed steel into a building block of modern civilisation. Carnegie Steel was a classic full-stack startup - they manufactured and distributed the steel. And they executed at startup speed, in less than 20 years they went from building their first plant to making most of the world’s steel. The result was a generational company- in 1901 when Carnegie sold to J.P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel was a massive outcome: US$492m or ~US$20bn in today’s money.

The current wars were pioneered by two full-stack companies that transformed energy generation. Both Westinghouse and Edison scaled AC and DC-based power generation with full-stack companies at startup speed and generated large companies in the process. Edison had less success in generating value with DC given AC-based systems won, but the full-stack ideology lived on when he sold to General Electric, who ended up scaling AC-based systems with a full-stack approach and became one of the largest companies of the 20th century. AC remains the most common form of power generation today.

Today, there is an emerging set of climate industrialists proving full-stack climate is a business model to build a generational company: Solugen, Northvolt, Stegra, Form Energy.

Whilst there are many more emerging examples (I’ve got a list), so many industries need decarbonising. Physical industries are huge, roughly 35% of global GDP or >US$80trillion per year revenue. History shows the adoption of novel technology increases the total size of an industry. The size of the prize is big for many large full-stack climate startups to be built.

The risks of these companies are obvious: most discussed being the capital required. I plan to write more on this topic given my background across vc, pe and infrastructure.

But stepping back, if we think about “desirable destinations”, I think the most compelling path to becoming a truly large company that transforms a physical industry is by being a full-stack climate company. If you’re a founder building a pre-seed/seed full-stack climate company that’s looking to transform a physical industry, I’d love to hear from you.

Power is the potential to realise persistent differential returns, even in the face of determined competition.

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts on the capex to first revenue and FOAK context for full-stack startups!